The Curious Experience of Nasal Breathing: A Deep Dive into Human Perception

When we think about breathing, it often feels like a straightforward, mechanical process: air flows in through our nose or mouth, fills our lungs, and sustains life. Yet the subjective experience of nasal breathing is anything but simple. For millions around the world, the sensation—or disruption—of nasal airflow can heavily impact comfort, sleep, and even emotional well-being. Surprisingly, this perception is not merely about how much air passes through the nostrils, but also how the nasal mucosa “feels” that airflow.

Recent research sheds light on the complex sensory and psychological mechanisms underlying nasal breathing. Understanding this can not only reshape how we view common complaints like nasal congestion but also revolutionize treatments for conditions like chronic rhinitis/ rhinosinusitis and empty nose syndrome.:

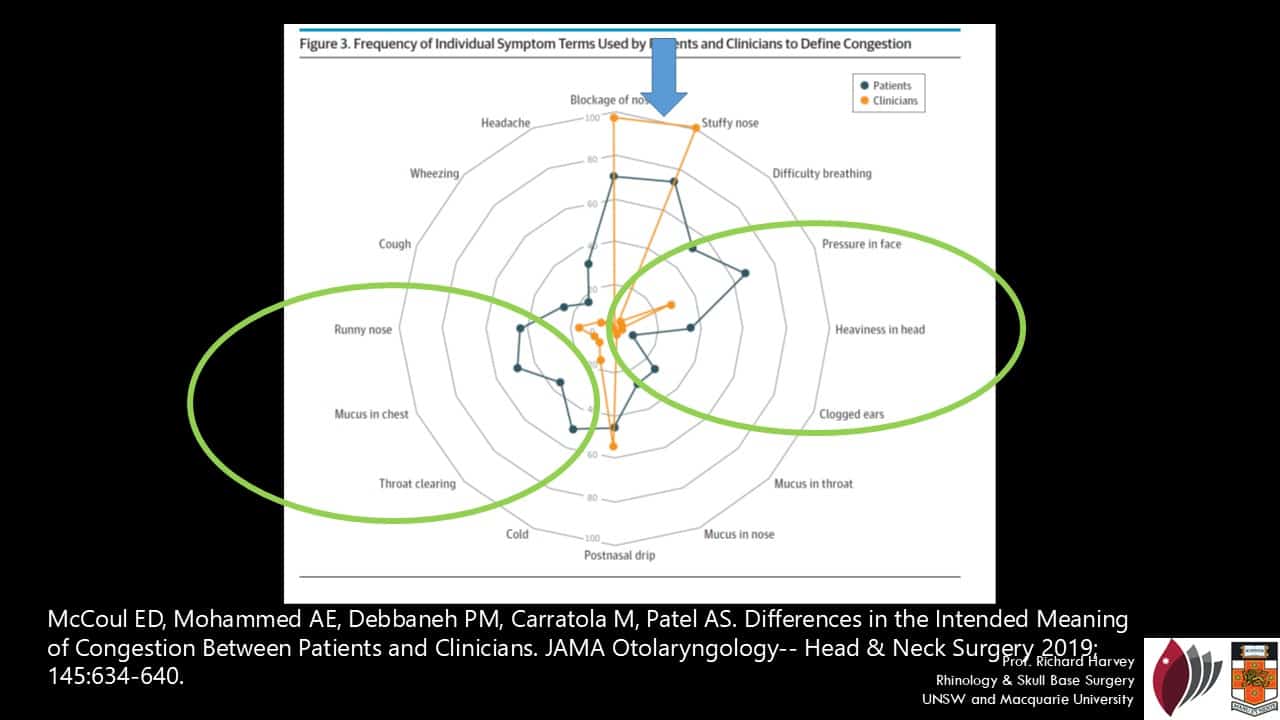

Interpreting Nasal Congestion: Bridging the Blockage vs Pressure/Mucus Divide

The symptom of nasal congestion often reflects a striking disconnect between patient and clinician interpretations. McCoul et al. (2019) revealed that while clinicians narrowly define congestion as nasal blockage due to mucosal swelling, patients frequently describe congestion using a much broader palette of sensations—including facial pressure, mucus accumulation, and even headache.

Critically, the study found that patients were 39% more likely to associate congestion with pressure-related symptoms and 51% more likely to relate it to mucus symptoms compared to clinicians. For example, 50% of patients identified “pressure in the face” as part of congestion, compared to only 16% of doctors. Similarly, “postnasal drip” was tied to congestion by 38% of patients but merely 3.5% of clinicians.

This discrepancy highlights a clinical pitfall: if physicians focus only on airway patency and physical obstruction, they may miss the true sources of patient distress. As Harvey et al. (2024) further emphasized, “nasal congestion” is often an umbrella term encompassing blockage, pressure, mucus, and even pain. Anatomical evaluations and airflow measures like rhinomanometry may therefore fail to capture the complex, multifaceted experience patients report.

Effective communication is crucial. Physicians should actively inquire whether a patient’s “congestion” refers to airflow restriction, facial pressure, or mucus-related symptoms. Tailoring treatment accordingly—whether decongestants, anti-inflammatory therapies, or mucus modulators—can dramatically improve satisfaction and outcomes.

In summary, nasal congestion is not synonymous with obstruction. Addressing pressure and mucus symptoms alongside physical airway management is essential for truly meeting patient needs.

The Anatomy of Perception: Airflow vs. Sensation

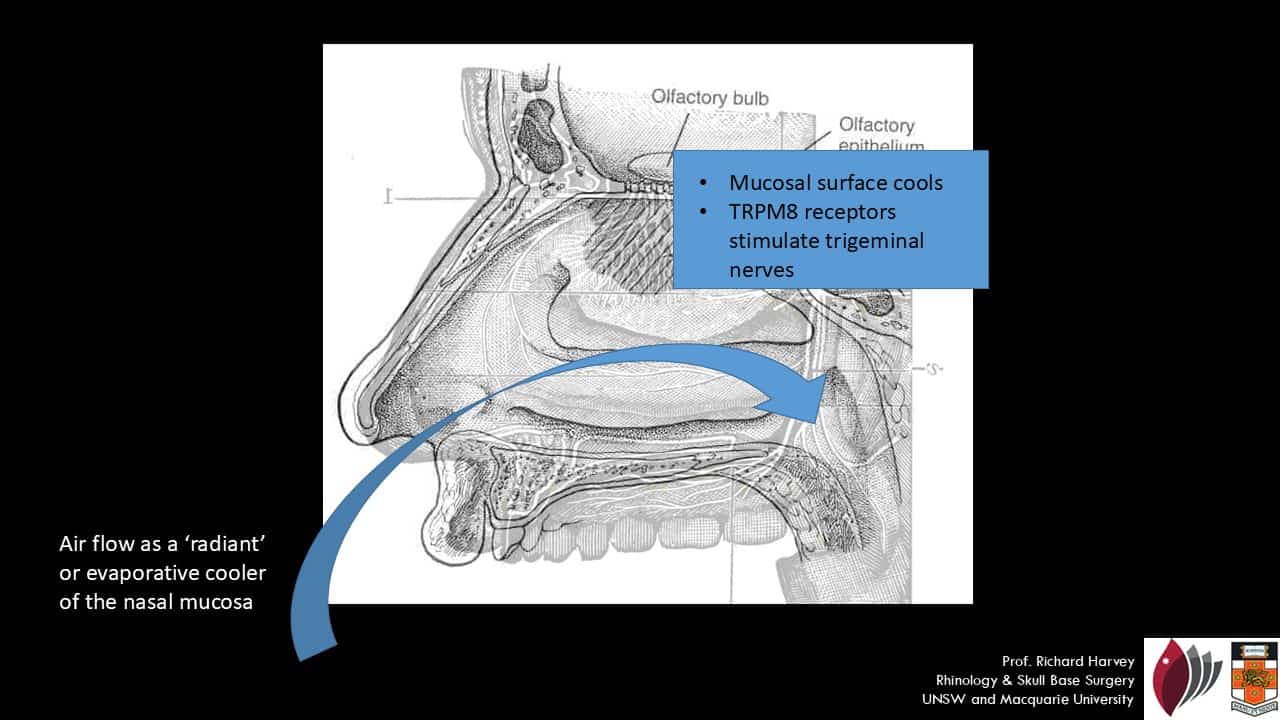

At first glance, one might think that the brain senses airflow in the nose directly. However, human nasal perception is primarily thermosensory, not purely mechanosensory. In other words, what we feel as “easy breathing” largely depends on how cool our nasal lining becomes, not necessarily how much air moves through the nose.

When air passes through the nasal passages, it causes evaporative and radiant cooling of the mucosal surfaces. This subtle temperature change is detected by specific nerve endings, particularly those belonging to the trigeminal nerve.

Interestingly, despite measurable increases in airflow after procedures like septoplasty or turbinate reduction, many patients still report persistent nasal obstruction if the mucosal cooling effect is not restored. Simple objective airflow measurements often correlate poorly with subjective improvements in breathing sensation.

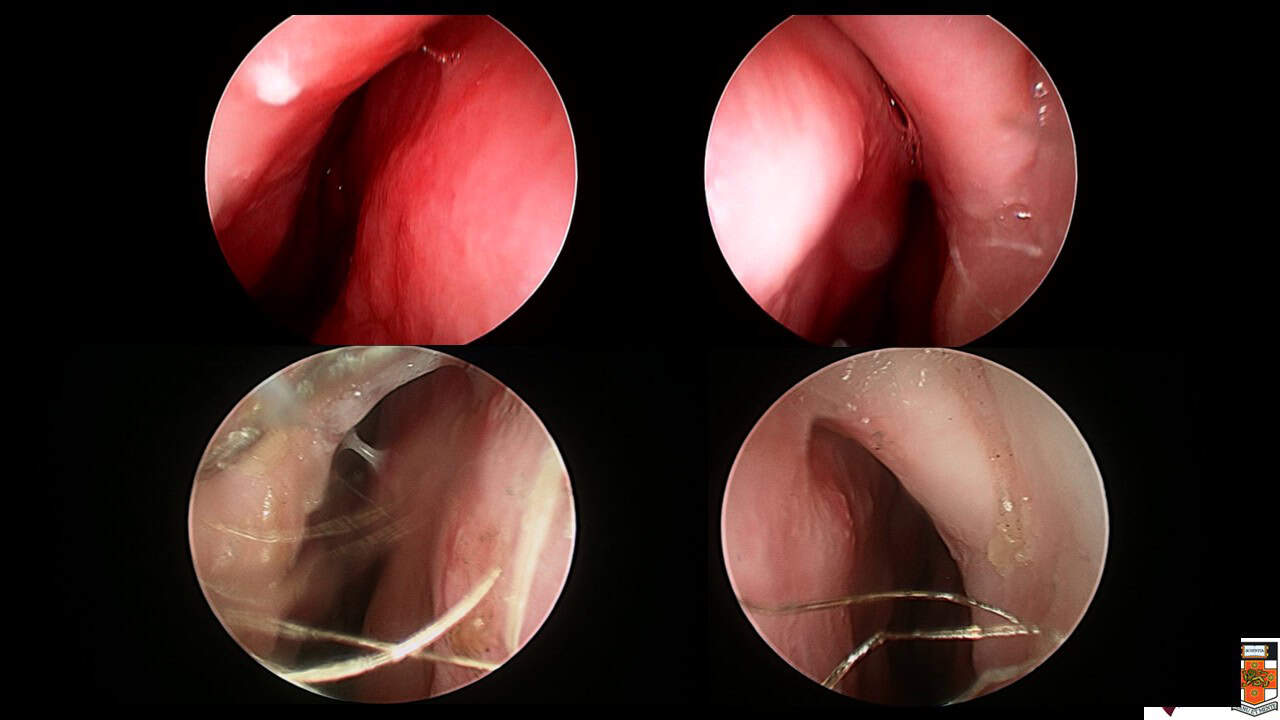

A high septal deflection on the left is relatively minor but prevent airflow to the upper part of the left nasal cavity and brings about a disproportionate sense of nasal obstruction compared to the anatomical cross-sectional area comprimsed by that anatomical abnormality

Thus, enhancing mucosal cooling—not merely enlarging airway diameter—is critical to optimizing the subjective nasal breathing experience.

TRP Channels: The Molecular Guardians of Nasal Sensation

The key players in detecting nasal mucosal cooling are transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, a family of ion channels involved in sensory transduction.

TRPM8, a specific subtype of TRP channels, is particularly crucial. It responds to:

- Temperatures between 8°C and 22°C

- Chemical agents like menthol and eucalyptol

When activated, TRPM8 channels stimulate sensory neurons that transmit signals to the brainstem and cortex. This leads to the subjective experience of “clear” and “easy” nasal breathing.

It’s why mentholated lozenges, nasal sprays, or even cool air can create a powerful illusion of improved nasal airflow, even when objective measurements remain unchanged.

TRPM8 receptors are located predominantly on trigeminal nerve endings within the nasal epithelium, mucous glands, and vessels, making them essential sensors of the nasal environment.

How Cooling Becomes Consciousness: The Neural Pathway

Once the TRPM8 receptors are activated by cooling, they:

- Depolarize sensory neurons

- Send signals to the spinal trigeminal nucleus

- Cross over to ascend the trigeminospinothalamic tract

- Activate higher brain regions such as:

- The insula cortex (emotional processing)

- The anterior cingulate cortex (attention and decision making)

- The somatosensory cortex (sensory mapping)

- The precentral gyrus (motor control)

This complex neurocircuitry illustrates why nasal obstruction isn’t merely a physical complaint. It deeply ties into emotion, cognition, and even motor readiness, explaining why nasal blockage can feel so distressing and distracting.

Beyond the Nose: Anxiety and the Sensation of Air Hunger

An often overlooked factor in nasal perception is the role of psychological states, particularly anxiety.

Feelings of “not being able to breathe” strongly overlap with symptoms seen in anxiety disorders:

- Air hunger

- Dyspnea

- A sensation of suffocation

In conditions like empty nose syndrome (ENS), patients paradoxically feel congested despite having wide, open nasal passages post-surgery. This mismatch between objective nasal patency and subjective breathing difficulty is thought to involve maladaptive cortical processing, especially in the emotional centers of the brain.

Thus, treating nasal obstruction might, in some cases, require a dual approach:

- Physical: Correcting anatomical issues and restoring mucosal cooling

- Psychological: Managing underlying anxiety or sensory integration disorders

Clinical Implications: Reframing Treatment Goals

Traditional interventions for nasal congestion have heavily focused on restoring airflow. However, newer insights emphasize that restoring mucosal cooling sensation is just as, if not more, important.

Strategies include:

- Create mucosal separation throughout the nasal cavity during surgery to enable evaporative cooling

- Treat underling inflammatory mucosal disease

- Avoiding offering surgery to patients that have enormous expectations of benefit to fatique, sleep and energy levels

- Screening patients for anxiety or emotional dysregulation pre- and post-surgery

Furthermore, in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP), effective treatments like biologics (e.g., anti-IL-5, anti-IL-4/13 agents) not only reduce polyp burden but may also improve mucosal health, enhancing cooling sensation and breathing perception.

Emerging Therapies: Biologics and Beyond

In chronic inflammatory conditions like type 2 CRSwNP, biologics targeting eosinophils (anti-IL-5) or broader type 2 pathways (anti-IL-4/IL-13) are changing the landscape.

By reducing mucosal inflammation, they indirectly restore:

- Mucosal smoothness

- Normal vascular function

- Effective TRPM8 signaling

Clinical trials like SYNAPSE (mepolizumab) and dupilumab real-world studies have shown significant improvements in nasal symptom burden, often including improvements in breathing perception.

Yet not all patients respond equally. In non-responders, other factors like local allergen-driven IgE pathways, anatomic variations, or even psychological overlays may still drive symptoms.

Conclusion: Breathing is More Than Air

The experience of nasal breathing is a marvel of biological engineering, combining thermodynamics, molecular sensing, nerve transmission, emotional regulation, and cognitive interpretation.

Key takeaways:

- We perceive nasal airflow primarily through mucosal cooling, not sheer airflow volume.

- TRPM8 receptors play a central role in this perception.

- Anxiety and emotional processing significantly modulate how we feel about breathing.

- Effective treatment of nasal congestion must address both physical airflow and sensory restoration.

In embracing this holistic understanding, clinicians can better tailor treatments, improve patient satisfaction, and perhaps most importantly, restore the simple but profound comfort of a clear nasal breathing.

References:

- Harvey, R. J., Roland, L. T., Schlosser, R. J., & Pfaar, O. (2024). Chief Complaint: Nasal Congestion. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, 12(6), 1462–1470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2024.04.028

- Harvey, R. J. (2025). Managing different phenotypes in CRS: Unmet needs and the role of Biologics. Novartis Educational Session, Rhinology & Endoscopic Skull Base Surgery, University of New South Wales. [Internal document]